Mission Galápagos

The Finches, the Ritters and the Indefatigable Templeton Crocker

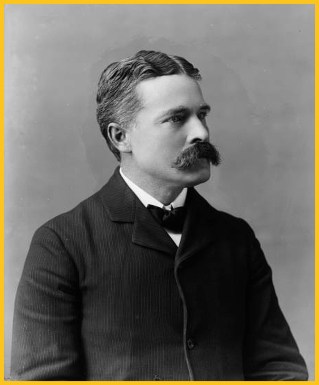

Charles Templeton Crocker on board his famous schooner Zaca

Two exhilarating travel books were written in the 1930s by famous Crocker cousins Aimée Isabella and Charles Templeton, about their breathtaking around-the-world journeys, taken nearly 40 years apart.

Aimée’s travelogue/memoirs are riddled with murder and mayhem, train wrecks and kidnappings, headhunters and shark attacks. The body count is frightening. In one grotesque scene a vulture drops the flesh of a human corpse down at the horrified heiress’s feet.

Templeton’s odyssey, on his schooner Zaca, was one of near bliss, of scenic intoxication, overtures with brown natives, and rampant sensory overload while commingling with a long list of palm-fringed islands—Marquesas, Societies, Cooks, Fiji, Samoa, Papua, the Trobriands, Bali, Singapore… If Aimée’s book was a gothic carnival of death, his was a watercolor wash of seashell lagoons and tropic sunsets. Templeton and his companions were seized by a languor on board his luxury yacht in between island hopping, at times luffing, loafing and dozing, often overdosing on plumeria scented fresh air.

One of Mr. Crocker’s few complaints was seeing overly civilized Tahitian dancers wearing picturesque native costumes over their regular clothes–white shirts, calico dresses and long trousers. He expected to see them perform in the altogether.

For amusement the Zacians enjoyed seeing natives react to modern inventions. The intense and unexpected cold of a refrigerator caused an indigenous chief to howl with terror. He was put under the shower and the water was turned on. He fled like a cat. A gramophone interested the tribal leader, but a Moritz Moszkowski violin solo was completely lost on him. He couldn’t understand the electric stove at all.

The climax of Templeton’s potboiler may be when he was face to face with a reported cannibal from the Nivambat tribe in the New Hebrides. There was no battle cry. No sailors held captive. No narrow escapes from natives wielding poison-tipped arrows. When Crocker offered a greeting and a handshake, the tribesman “withdrew his hand with a jerk, stepped back, snorted, and looked at me as if I were a boiled parsnip.”

In spite of the dearth of drama, it would be Templeton rather than Aimée who would enjoy universal praise from the critics for his offering The Cruise of the Zaca when it appeared in stores in 1933. It was in no way some dry contribution to either sociocultural anthropology or nautical science. While at times serious, it was considered a book of urbanity, a fantastical, exotic though genteel journey through wonderland after wonderland. Reviewers enjoyed Templeton’s meticulous and beautiful descriptions, his exquisite and sly sense of humor. They referred to him as a “master of anticlimax.”

The San Francisco Examiner wrote, “It is a simple, good humored account of a well dressed boat circulating among picturesque islands which are off the general ports of world travelers…. The style is as friendly as a letter home. The Zaca sailed smiling seas and the story is told with a smile that reflects the shimmer of Atoll lagoons.” The New York Times compared his work to best-selling South Seas travel writer Frederick O’Brien. The Zaca was compared to the illustrious HMS Challenger—the stalwart Pearl-class corvette that pioneered global oceanography in the 1870s.

The Expedition

On his return to California, Crocker complained of becoming restless, and that “the Zaca also was fidgeting at her birth.” He wrote, “I began to consider the possibility of an expedition with a serious purpose. Such a project was certainly no more inconceivable than had been my plan to own a yacht and go around the world on her. Furthermore a scientific expedition not only would be very interesting but would actually contribute something of value in this most political and rudderless world.”

Ward Collection, California Academy of Sciences, I.W. Taber, 1882

Templeton had friends at the California Academy of Sciences. Grandfather Charles established “The Crocker Scientific Investigation Fund” in 1881 for the Academy. The following year, Charles and partner Leland Stanford gifted the celebrated Ward Collection of scientific curiosities, which included fossil remains of strange creatures of former ages and of foreign countries; skeletons of snakes and birds; collections of skulls of different races; models of the habitations of the cave-dwellers; the head of half human Neanderthal man; a woolly mammoth sixteen feet high and twenty-six feet long.

That same year, Templeton’s great aunt Margaret (Aimée’s mother) donated her very rare and valuable collection of 1,500 birds and 100 mammals, including extinct Miocene birds and Pliocene horses, all of which were mounted, classified, suitably labeled, and arranged in glass cases.

Templeton’s father Col. Charles Frederick Crocker was the President of the Board of Trustees at the Academy from 1889 to his death in 1897. The Colonel had a voracious intellectual appetite. His driving dream as a young lad was to be a great scholar and nothing more. He confessed to newspaperman Walter Gifford Smith that in college he had a naive ambition, “to learn everything that man had known, to delve into all the lore of libraries and acquire all the learning of the universities.” C.F.’s eyesight weakened to a degree that he could no longer pursue his serious studies with the required intensity.

Col C.F. Crocker by Theo C. Marceau. Photo Courtesy of Tania Stepanian.

Both Colonel Fred and Uncle William, working in concert with the Astronomical Society of the Pacific and the Lick Observatory, underwrote scientific expeditions across the globe, timed to observe, measure and photograph the fleeting minutes of total solar eclipses. In 1922, a full decade before Templeton’s first expedition, William backed the monumental solar expedition to Wallal, Australia—an enterprise whose painstaking photographs bent the path of starlight and furnished the compelling data that verified experimentally Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity.

In 1905, their brother George backed a different kind of long shot—Commander Peary’s first push for the North Pole—where the compass spins wild and daylight never ends.

Templeton, the amateur thespian, librettist and divorced millionaire, decided that he had the time, the pedigree and the proper inspiration to not just fund a scientific expedition, he determined that he had all the right qualifications and the right vessel to lead an expedition. The San Francisco scion, met with Dr. Barton Warren Evermann, a renowned ichthyologist and the Executive Curator of the Academy and Director of its scientific activities.

Dr. Barton Warren Evermann (1853–1932)

Dr. Evermann outlined what he thought would be a most rewarding exploration that covered select islands off the coast of lower California and Mexico. Before long he was spinning a torrid spider’s web of tales that began with the magic words: Galápagos Islands. He spoke of the 76,000 specimens taken from the islands by the Academy during the 1905/6 Galápagos expedition, which had produced the most comprehensive collection and descriptions of the archipelago’s flora and fauna to date by far.

It was these endlessly fascinating isles that ensnared and tangled Templeton up in the Director’s elaborate plot. “The more he talked the more eager I became,” wrote the Crocker family book nerd and drama geek, “I wanted to start right off. Although quite bewildering, it was nonetheless fascinating.” He cast aside his looming trepidation. “What difference did it make whether one fell to the pavement from six or twelve stories?” he remarked.

Templeton asked for written instructions of all that Dr. Evermann wished his team of scientists to accomplish. He had every intention of contributing to the success of their ambitious assignments.

Treasure map of the The Templeton Crocker of the California Academy of Science, 1932

The instructions Evermann drew up read like a conjurer’s spell. In addition to the Galápagos, they were to visit Guadalupe, Clarion, Socorro, Cocos, Clipperton, Mazatlán, Cape San Lucas, and Magdalena Bay. As many specimens of pelagic (mid-water oceanic) fishes as possible were to be gathered for the Academy’s Steinhart Aquarium at Golden Gate Park.

They were to seek the possibly extinct Guadalupe petrel, record volcanic rumblings, dredge the sea floor, ascend the jungle peaks of Socorro in search of the rare and delicious bumelia fruit, and to comb the beaches of Acapulco in search of the Mitra belcheri shell, which hadn’t been collected since 1830.

A lake was said to be in the central crater at the highest peak of Indefatigable Island in the Galápagos. Should an opportunity be offered to make this most difficult inland journey, Evermann instructed that collections of plants, shells, diatoms and fishes be made. Templeton was most intrigued by this proposition because that locality had never been scientifically explored. It wasn’t certain, in fact, that anyone had ever been up there.

“No book of adventure ever gave me such a thrill as that letter,” wrote Templeton who had among the rarest and most important collections of books about the journeys of famous explorers of world history. To Crocker, a member of one of the richest families in American history, it was the greatest treasure map of all time.

And so Zaca was refitted not for leisure but for science. Ten galvanized tanks for live fish, thousands of feet of dredging wire, silken nets, zinc preservative boxes, collapsible boats… Captain Garland Rotch, who designed Zaca and took her round the world, led a crew of thirteen sailors. A scientific staff assembled: Harry Swarth, mammalogist and ornithologist; Walton Clark, ichthyologist; John Howell, botanist; Robert Lanier, Assistant Superintendent of the Steinhart Aquarium; and Toshio Asaeda, artist-taxidermist-photographer fresh from a Zane Grey South Seas fishing expedition.

Maury Willows, Jr. was Templeton Crocker’s secretary throughout the 1930s. He went on all of Crocker’s expeditions as the company ichthyologist. Photo courtesy Deborah Lashover.

Templeton’s personal secretary Maury Willows joined the party. He was a good conversationalist with a sense of humor and would help to keep the conversation from drowning in scientific discussions and anecdotes. He was put in charge of entomological collections. Maury’s diligent foraging resulted in the acquisition of 2,400 insects, adding new species and subspecies to the catalogue of insect fauna.

Maury played the role of likeable go-between, co-host and emotional anchor for the millionaire who often felt out of place with the sailors, out of his depth with the scientists, and far outside of his comfort zone geographically.

The Galápagos

Their ultimate destination, the Galápagos, loomed as a paradox: desolate and lush, desert and jungle. The rocky shoals and densely clustered outcroppings of flora on these volcanic islands, some 560 miles due west of Ecuador, owes its extraordinary character in part to the tropical Panama Current, which sweeps southwest, colliding with the cold, nutrient-laden Humboldt Current rising from the Antarctic. This singularly mysterious realm continues to serve up a perplexing blend of natural wonders, hidden terrors, and existential challenges to the modern mind.

Vast stretches of the Galápagos remain threadbare, nearly barren of vegetation. At lower elevations, the landscape is punctuated with conspicuously large cacti and thickets of mesquite. Mangrove trees line many of the shores, while higher, in the rain belt, dense jungles of towering trees and thick undergrowth prevail. On the highest summits, many square miles are either grass-covered or cloaked in sprawling ferns. The predominance of spiny and thorny plants and of those with thick, fleshy leaves or stems stand out in the flora.

There is little fresh water and no rain for more than half of the year, yet guavas, limes, coconuts, bananas, oranges, and avocados grow in profusion. Misty conditions prevail.

Thirteen active volcanoes on several islands pour out large areas of lava flow sending continual smoke signals to the baffling gods and warlocks who rule the land.

In 1535, their Spanish discoverer, Fray Tomás de Berlanga, reported to his king, “God did not make these islands for human habitation.” When Charles Darwin arrived on the H.M.S. Beagle three hundred years later, he found the Galápagos’ stark landscape hellish to behold. Herman Melville wrote of the Galápagos or “Encantadas” as “evilly enchanted grounds,” that refuse to harbor even the outcasts of the animal kingdom. “Man and wolf alike disown them. Little but reptile life is here found: tortoises, lizards, immense spiders, snakes, and that strangest anomaly of outlandish nature, the aguano. No voice, no low, no howl is heard; the chief sound of life here is a hiss,” he wrote.

Lieutenant Robert Mazet, in a U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings Report in 1938 wrote of the Galápagos that, “A sinister, malignant spirit seems always to pervade the land, beckoning yet deadly.” He cautioned, “to venture inland is to invite madness.”

The brooding equatorial archipelago—guarded by treacherous currents and scarred by fiery volcanoes—harbors a kaleidoscopic wealth of wildlife surpassing even the Rockies and the African veldt. Here, the scaly iguana shares the zoological limelight with the colossal tortoise. Repellent yet fascinating, these horny-hided, long-tailed giants—adorned with a saw-toothed ridge of keratinous spikes—are, save for the Komodo dragon and the crocodilians, the largest living heirs of the reptilian age.

The only land mammals, other than endemic Galápagos mice, also known as rice rats, are feral cattle, goats, donkeys and hogs, descendants of animals liberated by the conquistadors centuries ago. These wild, free-range livestock roam alongside the antediluvian reptiles, once domesticated, now evolving in reverse. They invariably are wary of man, while the native denizens, strangely, show no fear. Many have marveled at how the tropic birds will alight upon the traveler’s shoulder and how the sea lion will eat out of one’s hand.

Feral donkeys, cattle, pigs and goats compete with the Galapagos tortoise for food and trample nesting areas. Photos by Tui De Roy. Due to their diets and environment feral animals change physically, behaviorally & mentally. Feral pigs, for example, will grow more hair, become more aggressive and even grow battle tusks. They have the same genes as domesticated pigs, only expressed/activated differently.

The abundance of marine life in the Galápagos waters grow larger than the same species commonly caught on the eastern coast of the United States. A 200-pound tuna, a 60-pound wahoo, a 30-pound dolphin are not unusual. Kingfish, jacks, grouper, Spanish mackerel, and the ubiquitous barracuda are plentiful. Sailfish and marlin, stingrays and giant manta rays swim beside a terrifying abundances of tiger, hammerhead, Galápagos and cat sharks. In 1930, visiting yachtsman Eugene McDonald told the tale of fighting off great schools of sharks with machine guns. “They were so thick that we were afraid they would endanger the yacht. We killed hundreds of them,” he said.

Actor John Barrymore with his new bride Dolores Costello and an iguana at their honeymoon in the Galápagos. Barrymore was in his twenties chief crony and best friend of Aimée Crocker’s third husband Jackson Gouraud.

By the 1920s, the Galápagos had begun to draw a curious parade of naturalists, wealthy patrons, and touring celebrities—each with markedly different aims. Alongside McDonald’s Mizpah and Templeton Crocker’s Zaca, the sleek yachts of Vincent Astor, William Vanderbilt, William Mellon, G. Allan Hancock, and Harrison Williams threaded the treacherous channels. In 1929, Gifford Pinchot—Governor of Pennsylvania and widely hailed as the father of American conservation—came under the auspices of a Smithsonian expedition. Actor John Barrymore made the islands the unlikely setting for his honeymoon with Dolores Costello. President Franklin D. Roosevelt arrived in the summer of 1938 aboard the USS Houston on what the press styled a “Presidential Cruise.” Roosevelt caught a shark; Astor lost a finger feeding an iguana.

As a result of these visits, a group of wealthy U.S. families proposed the acquisition of the Galápagos Islands for its use as a game preserve. The plan was published in the Chicago Sunday Tribune in 1930 in an article entitled “How to Buy the Galápagos?”

Aimée Crocker’s memoirs had been thick with menace, Templeton’s were full of anticlimax. But in his second voyage, under Evermann’s spell, he sought something else altogether: not peril, nor luxury, but knowledge itself.

The Finches

Galápagos Darwin Finch by Simone O’Brien

The Templeton Crocker Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences set sail on March 10, 1932. Its namesake sponsor admitted he was hardly a man of the sea, “I am not a scientist, I know little of sailing, the sea rather terrifies me, and I am not insensible to any abnormal motion of the deck, which I have often paced wondering how on earth I ever got myself into such a situation.”

Templeton’s aversion to sea travel likely stemmed from his grandparents who survived one of the worst shipwrecks of 19th century, the SS Central America catastrophe in 1857.

Crocker noted, “A doctor is always on board, and I have a prayer book for emergencies.”

With great fervor and reverence, Naturalist-in-Charge Harry Swarth would make the holy pilgrimage to the Galápagos archipelago “Evolution’s Workshop” in search of his scientific enlightenment, like many a learned man before him, hoping to resolve outstanding questions posed by Charles Darwin in his theory of evolution, or perhaps to rework, unravel or dismantle it all together.

Swarth found bird life on the Plutonian island chain to be astonishingly abundant and colorful. He recorded and classified a long list of the archipelago’s avifauna, including the pink flamingo, the brown pelican, the blue-footed booby, and the man-o’-war.

Dwarf Galápagos penguin on board the Zaca, by Toshio Asaeda, Floreana Island, 1932, © National Museum of Ethnology, Japan, All rights reserved. X0076184

In these remote equatorial islands, thousands of miles away from their normal Antarctic and sub-Antarctic breeding grounds, he found dwarf penguins—scarcely half the stature of their southern relatives. Equally remarkable were the flightless cormorant that Swarth observed, equipped only with rudimentary wings, a striking departure from the strong and capable fliers of the same genus found elsewhere.

By the use of the freezing equipment installed aboard the ship, Mr. Crocker was able to bring back a number of these extraordinary birds to California.

It would be the Geospizids, the finches, that were of exceptional interest, capturing Swarth’s attention not only because of their many remarkable peculiarities, but because the study of them was largely responsible for the formation of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution.

Despite holding neither a doctorate nor even a bachelor’s degree, no one was better fitted to unravel the mystery of these singular birds than H.S. Swarth.

An authority on the avifauna of Arizona and the strange, wind-scoured coasts of the Pacific Northwest, he turned in 1927 to a systematic study of the Galápagos finches. He studied Stanford’s collections from the old ’89 and ’99 voyages; the great haul of 8,691 skins brought home by the California Academy’s 1905–06 expedition; the Rothschild Collection of Birds at the American Museum of Natural History; and, most precious of all, the very type specimens Mr. Darwin had collected while on his round-the-world cruise on the HMS Beagle at the British Museum (now the Natural History Museum at Tring). With Templeton, Swarth at last had the opportunity to study the finches of the islands in their own habitat.

Like Newton’s apple represents gravity, Galápagos finches have become universal symbols of Darwin’s theory of evolution. Illustrations from the book Zoology of the Voyages of H.M.S. Beagle, edited by Charles Darwin.

Swarth found himself circling one of the very questions that had so troubled Mr. Darwin when first advancing his then controversial theory of evolution through natural selection:

Why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion, instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined?

Their beaks—thick, thin, heavy, delicate—were as various as tools in a workshop, each form hinting at a different way of life. When Darwin first set foot on the remote Galápagos in 1835, the birds varied so much he failed to realize they were all finches. Swarth classified thirty-seven species and subspecies in six genera, convinced the entire assemblage had sprung from a single adventurous mainland ancestor once freed from continental competition. He thought that the ground finches of both the Galápagos Islands and Cocos Islands were so bewilderingly different from the standards applied to continental species that he felt obliged to cast them into a family of their own: the Geospizidae.

Swarth broke with Darwin. Instead of seeing natural selection at work, Swarth saw flux and drift—innumerable transitional forms without obvious advantage, creatures flourishing not through brutal struggle but because the rarefied Galápagos landscapes offered refuge from it. Survival of the fittest be damned. The great ornithologist hypothesized that these birds furnished one of the most striking illustrations in science of what can happen when a creature escapes from the keenly competitive life on a continent and is set loose into the more secluded conditions of an island world that offers a wealth of alternative opportunities free from brutal rivalries.

Harry S. Swarth, Naturalist in Charge of the 1932 Templeton Crocker Expedition

Modern science paints a different picture. Researchers now recognize fifteen distinct species, with roughly one in ten birds being (mostly sterile) hybrids. Studies suggest that beak size shifts with droughts, extended rainy seasons and “inter-species” competition. Natural selection, not chance mutation alone, is the prime mover.

Darwin introduced a radical, heretical, new picture of life. He overthrew special creation claiming the origin of species is natural not divine. He challenged the idea that God created each species perfectly and immutably.

Swarth, in turn, challenged Darwin’s belief that natural selection was a painstakingly slow process. On that point, modern science has sided with Swarth. Peter and Rosemary Grant, after decades of fieldwork, revealed that evolution in the Galápagos can be breathtakingly swift—sometimes visible within a single generation.

This is an image of the new Big Bird lineage, which arose through the breeding of two distinct parent species: G. fortis and G. conirostris. Photo by Peter Grant.

What stood out the most from the 1932 voyage was not taxonomic wrangling but conservation. After returning from his life altering Zaca trip, Swarth urged Ecuadorian authorities to preserve the islands, warning that colonization threatened the balance of rare and delicate flora and fauna in soils ill-suited for farming. The climate was fickle, the rainfall unreliable, and the soil unkind to cultivation; safeguarding the peculiar species that made the Galápagos unlike any other place on earth was paramount.

“Factors influencing variation have operated on this spot in a universal, deep-seated and spectacular manner such as can hardly be found elsewhere,” he pleaded. His vision—of the Galápagos as sanctuary and living laboratory—eventually prevailed. Today ninety-seven percent of the archipelago is protected as a national park and wildlife sanctuary managed under the guidance of a research station that bears Darwin’s name.

Out of Crocker’s pilgrimage, with his prayer book in hand and Harry Swarth as high priest, came an endeavor that helped shape both the science of evolution and the global conservation movement.

The Garden of Eden

Templeton showing off his shark trophy, Floreana Black Beach, 5-20-1932, Photo by Toshio Asaeda © National Museum of Ethnology, Japan, All rights reserved, X0076139

On their return from the expedition, the Associated Press published photos of a 10’6″ 805 lbs. tiger shark that the Zaca crew brought back. The press was not interested in the newly categorized species collected during their scientific journey, or Swarth’s finches, or the Origin of Species.

They didn’t trumpet Swarth’s campaign to protect the fauna and flora of the Galápagos Islands from settlement and the introduction of invasive species.

What generated the most headlines from coast to coast was that the Zacians and their guest scientists met the famous Adam and Eve castaways, Dorothea “Dore” Strauch Körwin and Dr. Friedrich Ritter, who lived carefree and unclothed on the deserted Floreana Island (then Charles Island) in the Galápagos chain.

The German immigrants moved to the island two years prior and found it “the most inhospitable ground that human feet could tread upon.” Yet they rejoiced in all its hardships, embracing the relentless labor and deprivation as a path to something higher. Like modern anchorites, they withdrew from the comforts and vanities of the world, striving for spiritual perfection and the absolute triumph of mind over matter.

“Each passing day convinces us anew that there are lasting satisfactions to be derived from this natural strife, which for us has taken the place of the sordid and unnatural struggle between man and man that marks so-called civilization,” wrote Ritter in an Atlantic Monthly article.

They called their settlement Friedo—a merging of their own names, yet also a quiet homage to Frieden, the German word for “peace,” a promise of serenity amid the harsh wilderness.

Crocker found the couple hard at work rearranging the geography of their garden home by diverting a stream to clear the site for a new house. Dr. Ritter’s principal difficulty, Crocker said, had been to devise means of keeping wild pigs and insects out of his cultivated land. They were, of late, experimenting on the effects of light and uncooked food on the human system.

Übermensch Friedrich Ritter and Überfrau Dore Strauch on board Zaca, 1932

Their house, a mile and a quarter from the beach, had a galvanized iron roof, was about 30 feet square and open on two sides. One corner was screened off as a bedroom; along the walls, shelves sagged under the weight of books, papers, and magazines. A veranda of flat stones at ground level served as their living room, stretching at one end into the open-air kitchen, where a tap of running water and a sturdy stove—gifted to them by the visiting yachtsman G. Alan Hancock—gave the place its touch of modern comfort.

“We came to live a life of contemplation, of mutual love and simple work with natural things. We shall stay here always,” Friedrich declared. Photo taken by Toshio Asaeda during Crocker’s 1932 expedition for the California Academy of Sciences. © National Museum of Ethnology, Japan, All rights reserved.

The Ritters had turned their backs upon the refinements of overcivilized man, only to fall into pronounced contention with a lawless posse of wild cattle, wild swine, wild asses, wild dogs, and wild tabby cats, each gone feral over the centuries. They disturbed the island peace with their nightly devil’s chorus of braying, squealing, howling and screeching while feeding and fighting, and making rowdy love. The vagrant beasts ranged over the whole island and seemed to resent the intrusion upon their preserve. Friedrich elaborated, “In this warm clime, where the pulse of life beats quick and fast, the battle to survive becomes an unending state of war between man and the wilder forces of nature.”

The Friedo estate included a native garden that contained bananas, papayas, oranges, coconuts, guavas, lemons, and pineapples, as well as a species of yam that grew quite large. In a cultivated plot they planted all the common varieties of vegetables, including beans, tomatoes, cabbages, peas, beets, potatoes, radishes, cauliflowers, onions, celery, and spinach.

Photo taken on board the G. Alan Hancock’s Valero III. Hancock was a Los Angeles tycoon who donated the La Brea tar pits to the city. He was also a touring cellist.

By the doctor’s reckoning, they had moved no fewer than two thousand barrow-loads of earth and rock. For a while they had a donkey—a wild burro re-domesticated—that lent its strength to the herculean gnome and his steadfast Girl Friday in their ceaseless labors.

In time, Friedrich and Dore learned what it meant to live in harmonious accord with nature. Every object in Friedo slowly became woven into their story: each stone, each tree, each patch of soil seemed to take on a personality—as though it embodied some portion of their toil, a fleeting thought, a benediction, or a curse.

Back in Germany

The Ritters’ nudist/vegetarian/desert island experiment was in some ways the most absorbing thing that the Zaca scientists discovered. They certainly warranted a full investigation.

Dore had fallen gravely and mysteriously ill a few years earlier. After a seventeen-month hospitalization at the Hydro-therapeutic Institute of the University of Berlin, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and told her illness was incurable. Dore found herself falling in love with Ritter, her attending physician, with “his astonishing blond mane, his youthful bearing, and his steel-blue eyes that looked out from under his furrowed forehead so compellingly.” He looked like the lyric poet Algernon Swinburne.

Strauch was preparing for a career in medicine, yet her heart beat more fiercely for the great German philosophers. Her affections wavered between the bleak clarity of Schopenhauer—“This is the worst of all possible worlds, for if it were any worse it could no longer exist as earth—it would be hell”—and the soaring optimism of Nietzsche, who countered, “This is the best of all possible worlds, for if it were still better it would no longer be earth, but heaven.”

In time, and under the influence of Dr. Ritter, Frau Strauch determined to remake her life according to the precepts of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. She became a strict vegetarian, vehemently opposing the destruction of life for human nourishment, and, when she met the good doctor, was experimenting with confining her diet exclusively to figs.

Friedrich, too, pursued the mysteries of diet, convinced that to master the problem of dietetics was to banish half the maladies that plagued humanity. Philosophically, he moved between two opposite poles—subscribing to Nietzsche’s Übermensch theory that one could overcome God and country or any debilitating obstacle, no matter how extreme, by sheer force of will, and Laotse, the serene prophet of going with the flow. Ritter somehow reconciled and married the tumult of heroic striving with the placid gospel of contemplation and acceptance.

Humorist and New Thought movement philosopher Prentice Mulford worked in the gold mines and wrote for the Golden Era beside Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Charles Warren Stoddard, Fitz Hugh Ludlow, Adah Isaacs Menken, and Ada Clare,

The prescription that he wrote for his new disciple Dore to address her physical symptoms and existential dilemmas was to read the works of American guru Prentice Mulford, chief influencer of the New Thought movement. He believed Mulford, a Gold Rush miner and humorist who was friends with Mark Twain and Charles Warren Stoddard, would carry her further along the path of spiritual evolution.

In volumes such as Thoughts are Things and Your Forces and How to Use Them, Mulford introduced and outlined metaphysical staples foundational to the movement like the Law of Attraction, the power of thought, spiritual self-reliance, mental healing, auto-suggestion, and personal magnetism. Mulford was among the first to argue that thought itself is a creative force—shaping not only one’s health but also the circumstances of life. The idea that her very thinking might be creative—that her inner life could alter her outer fate—offered Dore both bewilderment and a sudden, fierce hope.

Their attraction was so immediate, so inevitable, that their relationship seemed preordained; Dore and Friedrich were “wedded before they met.” Both, inconveniently, were already married—he to a Royal Opera singer in Darmstadt, she to an aging secondary school principal.

With a single kiss Friedrich made plain that he accepted the love she was harboring for him (though he confessed that he was carrying a torch for his own niece, 20 years his junior). To untangle themselves without scandal or heartbreak, they devised a seemingly farcical scheme: to pair off their more conventional spouses with each other. It worked.

Ritter opened up to Dore about his secret plan to “flee the beaten paths of man, put aside all the irrelevant trappings of civilization, and seek a solitude where I could at last live wholly and completely in contemplation and communion with nature.”

Dr. Ritter would leave a brilliant career in Germany, a professorship at Freiburg, and a chance for fame through his experiments in nutrition. Friedrich was reading at that time the Pulitzer prize winning novel Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis about a doctor who is faced with the dilemma of choosing profit and prestige over advancing scientific knowledge in the West Indies. He ultimately abandons the high-profile world of research for a quieter, more independent pursuit of pure science.

“I cannot have a love-sick woman full of romantic notions trailing after me into the wilderness,” Dr. Ritter would say reminding his protege, who was fifteen years younger than him, that their grand experiment would be all about self-empowerment. Dore fancied her doctor-lover as a John the Baptist who sought the wilderness, not in order to chastise the flesh but to illuminate the mind. Together they wanted to try and find an Eden not of ignorance but of knowledge.

Portrait of William Beebe from his best-selling book Galápagos: World’s End. about his expedition to the islands in 1923 sponsored by the New York Zoological Society

Strauch and Ritter brainstormed about where to settle. It was pioneering oceanographer and naturalist William Beebe’s landmark travelogue on the Galápagos that persuaded them to seek their idyll on the islands, a land so alien that it had never been inhabited by an indigenous tribe.

They also learned that the Ecuadorian government had decided to try colonizing the archipelago again. Settlers were invited to enjoy free plots of land with hunting and fishing rights and no taxes for ten years. The last traces of any kind of colony was a cadre of Norwegians who left Floreana after a short stay a couple of years before the Ritters arrived. Before them the island was a hideout for English pirates, a way station for whalers and a prison for Ecuadorian criminals.

Dore and Friedrich chose a little oasis in the crater of an extinct volcano at Floreana, high up on the side of a mountain overlooking the ocean. It was a natural amphitheater–fertile, luxuriant, ample for all their needs, and a fortress strong enough to defy intrusion. Their nearest human neighbors were more then one hundred miles away on the next island of the Galápagos group.

Templeton served the castaways a lunch fit for royalty on Zaca. The Ritters pushed aside the lobster curry with rice, but thoroughly enjoyed the mashed potatoes with butter, fresh baked bread and blueberry pie. The lonesome souls were moved to tears when Bach and Chopin records were played. Templeton reported that the doctor, in spite of commonly held beliefs, didn’t act or talk like a fanatic.

Crocker and crew gave the happy couple generous supplies of flour, sugar, soap, canned goods, ammunition for a Remington Kleanbore 22 (needed to scare away the feral swine), writing paper, typewriter ribbon, some medicines including Novocaine, and some old used motor-oil to kill the insects. Templeton also hid a sheath knife under a magazine when no one was looking.

Templeton returns Dore and Friedrich to their Garden of Eden. Photo by Toshio Asaeda. © National Museum of Ethnology, Japan, All rights reserved. X0076118

The Zaca leader told the press that the Ritter’s 24-month Thoreau/Walden Pond/John the Baptist experiment was an unmitigated success; that they had found freedom, contentment and happiness in Friedo beneath the blazing sun and soothing moon of the tropics. Dore was radiantly happy and Dr. Ritter was a man who at last had freed himself of cumbersome social annoyances and pettiness. “We shall stay here always,” they declared. Friedrich wrote:

The heaven on earth for which we are working is not some silly theologian’s dream of a golden city where all the creature comforts denied us in practical life shall be offered us for the taking. Our heaven is a pure state of mind, a sense of mental peace to be achieved through self-knowledge, and to this end our work contributes in the fullest degree. It may seem to others that we who have come so far in search of this heaven have only succeeded in discovering a very special kind of hell. True, we toil and moil against greater odds and bear daily a far heavier burden of labor than is required of most men and women in civilized society. Still, we regard our lot as the preferable one for us. We two are the absolute masters of our destiny as you who remain in Europe and America can never hope to be.

Still from Strauch, Ritter, the Wittmer family & the Baroness, Floreana Island, 1930s from the Allan Hancock Archives. Dore was thrilled to show off her new false teeth. Friedrich had all of his rotting teeth removed before they left for the Islands.

Wealthy yachters like Templeton stopping at Floreana Island in the early 1930s reported on the couple’s pioneering enterprise to the outside world. A widely read three-part narrative in the Atlantic Monthly about life on the island written by Ritter himself came out a few months before Crocker’s arrival. The news of a modern Adam and Eve discovered on the fallen land that was the Galápagos, created a sensation. That’s when the trouble began…

People the world over wrote letters to the Ritters begging to be allowed to join them and establish a community of “like-minded souls.”

Dore and Friedrich, who had come so far to find a solitude in which they could meditate and live their own lives free from the distractions of social intercourse were appalled by the prospect of having their retreat become a haven of refuge for all the misfits of the world. Their plan was to make it clear to any newcomers from the start that they wanted to be left alone and considered them intruders. Invasive species.

The Wittmer family from left: Heinz, Rolf (who was born on Floreana), Harry and Margret, 1933

The dream of life on a tropical island was especially appealing to Germans suffering the political and economic upheavals of the 1920s. Just a few months after Templeton’s departure, Margret and Heinz Wittmer fled Germany and arrived on Floreana. The couple had become fed up with the turmoil in their homeland, and at the same time were seeking a hospitable climate for their sickly and delicate 14-year-old son Harry. A doctor recommended two years in a sanatorium, but that was financially out of reach for Heinz then secretary to the mayor of Cologne. They hatched the peculiar plan to leave the unhealthy conditions of city life, the German mayhem, and live in the middle of the Pacific on an enchanted and temperate though desolate and nearly infertile island to give Harry a shot at healing.

The Wittmers got the message to stay clear of Ritter’s Roost. Dore and Friedrich found them dull and conventional but relatively harmless. The next group of settlers would be a different diabolical story.

The Baroness

In October 1932, three years after the Ritters and three months after the Wittmers arrived on Floreana, 39-year-old Austrian Baroness Antonia Wagner von Wehrborn Bosquet stormed the shores of Floreana with two younger lovers, Arthur Rudolph Lorenz and Robert Phillipson, whom Friedrich later dismissed as “servile gigolos.” The Baroness, an authentic aristocrat by way of her grandfather, was Viennese by birth but had lived most recently in Paris, where she left behind a husband and a bankrupt lingerie shop.

The bottle-blonde Baroness promptly proclaimed herself “Empress of Floreana” and announced grandiose, cockamamie plans to erect a Miami-style resort for visiting millionaire yachtsmen. The press christened her “Crazy Panties”—a nickname inspired by her penchant for silk shorts and the revolver that dangled from a cord at her waist. Among the island’s settlers she quickly sowed discord with a series of thoughtless indulgences: rinsing her feet in Heinz and Margret’s drinking water, embarrassing Dore with frank talk about sex, and scandalizing everyone by attempting to seduce nearly every man she met—including Friedrich and Heinz.

After setting up their polyandrous abode in their own version of Eden, the Baroness and her boys planted a sign in the harbor:

WHO EVER YOU ARE FRIENDS: Two hours from here is Hacienda Paradise . . . a little spot where the weary traveler is happy to find some rest, refreshment, and peace on his way through life. Life, this little bit of eternity chained to a clock, is so short after all; so let us be happy, let us be good. At “Paradise” you have no name but one, “friend.”

The Baroness stole the international spotlight. Disturbing rumors soon swirled about her fierce temper. Stories that she kidnapped a Norwegian sailor and held him prisoner for a night; that she shot a Danish man Arends, a handyman, with a revolver, penetrating his arm and striking him in the hip; that she had fled the City of Light after committing murder. Many other outrageous stories were told, embellished or invented by the Baroness herself.

The serpent had entered Eden…

Still from the short film The Empress of Floreana featured in the documentary The Galapagos Affair Satan Comes to Eden starring the Baroness and Ray Elliott. On April 22, 1935, G. Allan Hancock presented the film at Ebell Theater in Los Angeles. For at least one night, the Baroness was a star.

Ritter and Dore’s fragile order began to collapse under the weight of rivals and interlopers. Templeton Crocker’s bright narrative of scientific triumph and castaway bliss had curdled into something darker. Peace on both Friedo and Hacienda Paradise was soon completely lost. In the end two members of this cast would, in fact, die (one of thirst, one of food poisoning), and two would disappear without a trace, all under mysterious circumstances. A hotel would rise, but not by efforts of the Baroness.

For nearly a century, this Galápagos Garden of Eden affair has gathered investigators and inspired artists. Most recently, a full length feature film, Eden, directed by Ron Howard, and starring heavyweights Jude Law as Friedrich, Vanessa Kirby as Dore, Ana de Armas as the Baroness, Daniel Brühl as Heinz, and Sydney Sweeney as Margret has been produced for a world-wide release.

The all-star cast of Ron Howard’s Eden are Jude Law, Ana de Armas, Daniel Brühl, Vanessa Kirby and Sydney Sweeney

Indefatigable

Kermit Roosevelt and his wife Belle with a slain tiger, Nepal, 1925

In 1925 Kermit Roosevelt, every inch the heir to his father Teddy’s rough-and-ready legacy, posed with his wife Belle over a slain tiger in Nepal. The former president once recalled how his daring and reckless son had “stopped a charging leopard within six yards of him after it had mauled one of our porters.”

Five years later, he set his sights on a different kind of trophy. During Vincent Astor’s 1930 New York Zoological Society expedition to the Galápagos, Kermit attempted to reach the highest peak of Indefatigable Island—today called Santa Cruz. No explorer had ever mounted above a thousand feet or approached the center of this island, but Kermit and his crew felt up to the challenge.

His team made it past the cactus belt, through the tangled jungle filled with choking curtains of miconia, beyond open forest glades, before reaching a ridge twenty-one hundred feet above sea level, twice the current record but short of the top of the highest mountain.

Along the way Kermit was, like every visitor, shocked by the tameness of the native island wildlife and surprised the feral barnyard animals left behind that were so terrified of man.

It was a mosquito invasion that caused Roosevelt’s bedraggled and bitten group to retreat short of their goal.

Naturalist superhero and deep sea explorer William Beebe, who went on two expeditions to the Galápagos and later two with Charles Templeton Crocker, also failed miserably to reach the summit. He wrote about the daunting adventure:

Like most of the other islands, its lower zone was one solid cinder, dotted with scores of dead, cold craters, with sparse vegetation springing from cracks and crevices and existing only by a never-ending fight for water. Every step must be tested, else a four-foot sheet of sliding clinker, clanging like solid metal, would precipitate one into a cactus or other equally thorny plant. A careless scrape of a shoe and the sharp lava edges cut through the leather like razors… each clump of pseudo-grass gave off at a touch a host of seeds, barbed and rebarbed, and the effect on clothes and skin was like a hundred fishhooks. When one of these seeds had worked inside the clothing, it meant blood from fingers and body to pull it clear, while one or more spines usually broke off, to work their vengeance at some later time. Never have I known a worse country for forced marches.

A week after the famous yacht Zaca dropped anchor at Academy Bay, a natural harbor of Indefatigable Island, Templeton engaged an Icelander named Finsen to prospect a route that would lead to the never before reached highest point of the island. Finsen, after doing some extensive scouting, gave the Zacians a possible though harrowing route that could lead to the conquest of the peak. Crocker and his crew began their own assault on the equatorial Everest.

Before Neil Armstrong landed on the moon, popular naturalist William Beebe was America’s number one real life superhero. He beat world diving records on board his submersible “The Bathysphere.”

Like Beebe and Roosevelt, Crocker discovered that this mountaineering venture didn’t involve typical difficulties involving altitude, freezing temperatures, climbing equipment, strength and finesse. It was a matter of penetration, perseverance and endurance. Dense tangled thickets of dark green mangroves; lava fissures of great depth opening underfoot; thorn scrub woodlands; cactus forests with trees twenty to thirty feet posed like Javanese dancers were among the road blocks on this tropical obstacle course.

Along the way they got caught it a drifting fog. A sudden tear in the clouds revealed that they were standing on the floor of a giant crater. There were indications of recent volcanic activity. They discovered also that some recent flash flooding had carved natural stairways. Following these, they pressed on all the way to the summit and to victory.

The penetration of Indefatigable Island on May 9, 1932—the first ever ascent of the highest mountain, 864 meters or 2,835 feet high, was a crowning achievement, both personal and professional, for the Zacians and the scientists, and a transcendental peak experience for Templeton Crocker. The Galápagos mountaintop was named Cerro Crocker (Mount Crocker) in honor of the Zaca expedition leader.

Templeton (third standing from the left) and crew at the highest peak of Indefatigable Island, 1932. Photo by Toshio Asaeda. © National Museum of Ethnology, Japan, All rights reserved, X0076083.

Back on Floreana, Dr. Friedrich Ritter, the philosopher-hermit, grappled and studied, hypothesized and experimented. He investigated the sick and the healthy, the cultured and uncivilized, the wild, the domesticated and the feral. In Ritter’s anthropology, Templeton would have been classified as an overcivilized man. He was the epitome of what the doctor fled Europe to get away from. That is prior to their meeting in the Galápagos, which occurred after Templeton’s triumphant climb and before Dore and Friedrich’s tragic downfall.

Dr. Ritter in his study, Hancock Pacific-Galapagos Expeditions, 1933-1935, RU 007231, Box 89, Folder 4

Ritter wrote that “culture is only an aptitude acquired by training, just as tameness is acquired by the beasts in a circus; in both cases the surface gloss disappears as soon as the creatures are given back to their natural surroundings.” Dore and Friedrich came to believe that they were neither being tamed or untamed, but were harmonizing with the Galapagos, passing through culture to the wisdom of self-knowledge. “At the end of each day we have the satisfying sense that we have lived completely, with a full utilization of all our powers,” Dr. Ritter wrote.

The castaway couple’s wilderness utopianism and near-pantheistic natural theology didn’t stand the test of the Baroness. Templeton may have been better equipped to handle her arrogance and pomposity and may have known when to cut and run and move on to the next expedition.

Templeton Crocker became an officer in the Red Cross during WWII. Photo from the Charles Henderson Collection.

Charles Templeton Crocker underwent the customary husbandry of a San Francisco scion produced by the usual processes of selective breeding. His privileges were many: abundant family coffers, a Hawaiian sugar heiress for a wife, the obligatory Grand Tour through Europe, a mansion on the Peninsula… Cultivated, cultured and cosmopolitan, he was an award winning librettist fluent in French, and the proud keeper of a coveted, rare library devoted to the arts and sciences. By 1912 he had been formally recorded in The Ultra-fashionable Peerage of America, thereby confirming his place in the taxonomy of American high society.

In his mid-life, Charles Templeton Crocker, the exceedingly wealthy and pampered theater geek, seasick landlubber, bespectacled book worm, and Bay area Walter Mitty, somehow, miraculously evolved—faster than a Darwin finch—into a real life, honest to goodness, swashbuckling and seafaring adventurer, jungle tamer, mountain climber and South Seas scientist.

After his mission to the Galápagos, the already free-thinking Bohemian underwent a feralization. With his schooner Zaca, and his scientists and sailors by his side, a deeper Übermensch fierceness would be unleashed that would find expression on five more expeditions. He would become forevermore free range and untamed. ![]()

Selective Resources

“Back to her Adam’s Grave on the Island of Love,” Pittsburgh Sun Telegraph, Dec 21, 1941, pp. 57, 58, 61.

BioScience Oct 2003 vol 53, no 10.

“Crocker Group Science Hunt Comes to End,” Oakland Tribune, Aug 25, 1932.

“Crocker Party First to Scale Mountains,” Oakland Tribune, May 13, 1932, p25.

“Crocker Writes Entertainingly of His World Cruise,” The San Francisco Examiner, Aug 13, 1933, p14.

“Crocker Yacht Returns with Big Catch of Strange Fish,” Oakland Tribune, Sep 1, 1932, p17.

Dore Strauch, Satan Came to Eden, as told by Dore Strauch to Walter Brockmann, (Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York and London, 1936).

Edgardo Civallero, “Nourmahal: The photo album / Charles Darwin Foundation,” (Santa Cruz, Galapagos : Charles Darwin Foundation, 2023).

Edward Larson, “God and the Galapagos?” https://metanexus.net/category/type_essay/ Aug 27, 2001.

Eva Martin, Prentice Mulford: New Thought Pioneer, (London: William Rider & Son, 1921).

“Fine Travel Writing: The Cruise of the Zaca,” Democrat and Chronicle, Sep 10, 1933.

Friedrich Ritter, “Adam and Eve in the Galapagos,” The Atlantic Monthly, Oct 1931

Friedrich Ritter, “Eve Calls it a Day,” The Atlantic Monthly, Dec 1931

Frederick Oechsner, “Paradise Life Has Its Drawbacks, Say Physician,” The World News, Mar 3, 1931, p3.

G. Dallas Hanna, “Templeton Crocker Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences,” Science, Oct 28, 1932, pp376,377.

G. H. Harper, “A Critical Review of Theories Concerning the Origin of the Darwin Finches,” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 14, No. 5 (Sep., 1987), pp. 391-403.

“Galapagos Cave Man-Scientist Works ‘Racket’ on Yachtsmen, The Miami New, Feb 23, 1930, p2.

“German Pair Happy in Robinson Crusoe Life,” Nevada State Journal, Sep 4, 1032, p1.

Hadley Meares, “An Unsolvable Mystery: Captain Hancock and the Case of the Quarrelsome Castaways,” April 22, 2020.

Harry S. Swarth, “The bird fauna of the Galapagos Islands in relation to species formation,” Vol. IX, No. 2 April 1934 Cambridge Philosophical Society Cambridge, Massachusetts: University Press, April 1934

Henry E. Armstrong, “Beckoning Islands of the Tropics,” New York Times, Sep 3, 1933, pBR10.

Herman Melville, The Encantadas, first published in Putnam’s Magazine in 1854

How to Buy the Galapagos, Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1930, p14.

John Thomas Howell, Up Under the Equator,” Sierra Club Bulletin, v.27 n.4, August 1942.

Joseph Mailliard, “In Memoriam: Harry Schelwald Swarth 1878-1935,” The Auk, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Apr., 1937), pp. 127-134.

Joseph Slevin, “The Galapagos: A History of Their Exploration,” Occasional papers no. xxv of the California Academy of Sciences Issued December 22, 1959.

Kermit Roosevelt, “The Mountain Party on Indefatigable Island,” Bulletin New York Zoological Society, Vol. XX XIII, No. 4, July-August 1930, p156-163.

Lieutenant Robert Mazet, Jr., (M.C.), U. S. Naval Reserve, “Fisherman’s Paradise—Settler’s Hell,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, May 1938.

“Lonely Isle is Haven for German Pair,” Santa Maria Times, Apr 15, 1932, p1.

Mary Markey, “The Empress of the Galápagos Islands, Part I-IV” https://siarchives.si.edu/, June 7, 2011, Jul 12, 2011, Aug 9, 2011, Nov 7, 2011.

“Modern Adam and Eve Living on Sun Burned Pacific Ocean Island,” The Lima News, Feb 27, 1930, p5

“Nudist Find Freedom and Contentment in South Seas; No Worry on Food or Taxes,” The Press Democrat, Sep 6, 1932.

People and Culture in Oceania, 38: 35-50, 2022 Toward the Reutilization of Past Natural History Materials Regarding Tropical Marine Life in the Pacific Islands: Analysis of Watercolor Paintings by Toshio Asaeda from the Crocker Expeditions in the 1930s Norio Niwa* and Rebekah Kim*

“Physician, Girl Enjoying Nude Experiment on Isle,” San Bernardino County, Sep 4, 1932, p2

Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences FOURTH SERIES Vol. XXI SF CA Academy of Science 1933-1936.

“Strange Beasts and Reptiles Still Occupy Darwin’s Isles. Ecuador Urged to Establish Sanctuary on Galapagos Group in Pacific,” Detroit Free Press, April 3, 1933, p12.

“Swarth on a New Bird Family for the Galápagos Islands Reviewed Work(s): A New Bird Family (Geospizidae) from the Galapagos Islands by Harry S. Swarth,” Review by: W. S., The Auk, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Apr., 1929), pp. 259-260

Templeton Crocker, “INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT, The Expedition on the Yacht Zaca to the Galapagos Archipelago and Other Islands and to the Coast of Central America and Mexico March 10 to September 1, 1932,” Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, Fourth Series, Vol.XXI, (San Francisco: Published by the Academy, 1933-1936)

Templeton Crocker, Zaca Sails South, A Non-Scientific Diary, an unpublished manuscript held at the California Academy of Sciences.

The bird fauna of the Galapagos Islands in relation to species formation. Vol. IX, No. 2 April 1934 Cambridge Philosophical Society Cambridge, Massachusetts: University Press, April 1934

“The Mystery-Tragedy of Island Eden,” Charleston Daily Mail, Dec 30, 1934, p39.

“Urges Use of Galapagos,” The New York Times, Mar 21, 1933, p 15

Vincent Astor Hunts for Penguins while Vanderbilts Seek Marine Specimens The Oshkosh Northwestern, Jan 9, 1932, p8.

Vincent Astor, “Galapagos islands as mysterious as in Darwin’s day,” The Morning Call, Jun 22, 1930, p2.