Aimée Crocker’s Dancers–Part One

SOIRÉE DE LA DANSE EXCENTRIQUE

Tropical dances, tempestuous dances, dances filled wild, weird tumult; slow, throbbing dances that turn the soul on beam ends; danceless dances, suggesting the oriental, occult and devout; awakening, thrilling, maddening dances; dances in which the dancer sits down and dances with the feet and arms; turkey trots and Honolulu boola-boolas—all are on Mrs. Jackson Gouraud’s amazing winter program. ——— The Chicago Inter Ocean November 11, 1911.

Aimée Crocker Gouraud returned from an extended visit to Paris in the fall of 1911 and revealed the terrific extent of her program to awaken society from its dull lethargic trance and set all the crème-de-la-crème of the haut ton awhirl. She described some of the “tremendous sarabands, capricolas and artistic dream dances” that she had garnered from the four corners of the earth and intended to put in vogue among her friends. The offerings of the undisputed Queen of Bohemia exceeded everyone’s expectations.

The event of the Crocker season, which received press from coast to coast, was billed as Soirée de la Danse Excentrique, also The Dance of All Nations. Aimée greeted her guests arrayed as “La Nuit,” in night-sky-colored floating silk draperies, embroidered with diamond stars and pearls “that would clothe a baby and ransom a king.” The music for the event was composed by Baroness Von Groyss, who founded, along with Aimée, the International Artistic and Social Club. The extravaganza was one of Aimée Crocker’s crowning achievements.

A smattering of Aimée’s 150 guests who attended her Dance of All Nations soirée (photo courtesy Daniel and Lionel Milano Collection)

The masquerade ball began with La Mazurka Russe, danced by Genia Agarioff and Maurice Mouvet who both wore what resembled a short ballet costume. Next in the lineup, the Harem Glide, was performed amid the grinning bulbuls, pearl-eyed Buddhas, giraffe plants, naked nymphs suspended in heavy gilded frames, samovars, fountains and jeweled lamps of the glorious Crocker five-story townhouse which resembled the interior of a genie bottle, or one of the apartments of the Sultan of Turkey.

The Siberian Whirl was danced by Harry Pilcer and Kathleen Clifford who were then dazzling Broadway in the musical comedy Vera Violetta at the Winter Garden with music by George M. Cohan. The hit show also showcased the talents of superstar Gaby Deslys, Mellville Ellis (who along with Agarioff would be linked to Aimée romantically), Al Jolson and an eighteen-year-old Mae West. Vera Violetta would introduce a world wide dance craze with the “Gaby Glide.” Gaby and Broadway star Raymond Hitchcock were among the 150 people present at Aimée’s sensational shindig.

Legends Harry Pilcer and Gaby Deslys both attended Crocker’s Dance of All Nations. Pilcer danced the Siberian Whirl.

Actress Nance Gwynn danced topless as Salome at the Dance of All Nations

Nance Gwynn, the Australian actress, representing ancient Judea, “Salomed” herself out of her costume in the epic Dance of the Seven Veils, a number out of Oscar Wilde’s play Salome widely considered the first striptease act in show business. She dashed about in a wild whirl to the music of the “Woodland Dance,” composed for the occasion by Baroness von Groyss.

The Baroness danced the curious Vienna Viggle.

Another headliner was “headhunter” dancer Dogmeena, whose costume consisted of chocolate colored trunks, coconut oil and a red sash. She enthusiastically danced in La Danse des Igorrotes. Dogmeena, a discovery of the flamboyant Baroness, created a sensation when she dashed into the drawing room furtively, bearing a spear. She then savagely swayed from side to side until a rhythmic ecstasy of destruction was reached, and finally she plunged her spear at an imaginary head on the floor, thus becoming a tribal chieftainess.

Of all the new dances that Mrs. Gouaud was hyping, she was most passionate about the Honolulu Kui, aka the Hula Ku’i. Six Kanaka maidens and two men danced the Kui for Mrs. Gouraud’s illustrious guests. The ancient hulu variation was first resurrected by King Kalakaua of the Sandwich Islands (now Hawai’i) at his inauguration after being banned for 50+ years. In Aimée’s interpretation, as the dancers whirl and shimmy, they dance the leaves off their skirts one by one (not unlike Salome dancing off her seven veils).

That evening Crocker also introduced New York society to the Tonga dance. She described its impact:

The poetry of this dance overwhelms the soul with rapture. There is a maddening rhythm to the grace of movement. You are translated to the golden shores of far Tahiti, to a superheated mystic fairyland, as it were. Your entire being becomes saturated with soul poetry. Your senses are dead. You might as well be a red hot atom hurtling through space, dodging stars and moons and ringed Saturns. How poor a stimulant is even wood alcohol compared with the intoxicating influence of the Tonga dance.

Aimée and Genia Agarioff dance an Argentine Tango at The Dance of All Nations

The star dancer of the evening was Mrs. Gouraud herself. She delighted the company when she danced La Madrilena, an Argentine tango, with one of her most recent admirers, the handsome Agarioff, who was an opera singer as well as a dancer. Two years later, Pope Pius X would declare the tango as immoral and off-limits to Catholics. He insisted that anyone who performed the dance go to confession.

A little later, with a twelve foot snake twined round her neck, Aimée appeared in La Danse de Cobra. When her guests backed away later from the snake’s emerald eyes and darting tongue, she exclaimed, “It’s as gentle as a powder puff.”

Crocker dancing with Kaa at The Dance of All Nations

The snake was on loan from Princess Sita Diva, who performed the dance a week earlier at Edmund Russell’s pink tea at No.40 W. 39th St. The python was touted as a lineal descendant of Kaa in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book—the one that devoured young monkeys in the moonlight of the ruined city of Seonee. Russell, heralded as “The Apostle of Delsarte,” “The Apostle of the Beautiful,” and the “American Oscar Wilde,” was working on a portrait of Aimée Crocker Gouraud which would be unveiled in the coming months. Russell and Crocker worked in tandem to entertain the Bohemian/Broadway set of New York society that winter.

Among the vaudeville stars and writers that they dazzled, there was always a gaggle of gaikwars, some ahoonds, more than a few Mustaphas, several princesses, barons and counts and at least one chary-eyed preacher. Russell was an actor and a dancer himself who played King Dushyanta in a single performance of Sakuntala with modern dance pioneer and Delsartean Ruth St. Denis at the Madison Square Garden Concert Hall on June 18, 1905.

Dance Legend Isadora Duncan, born in San Francisco, was a family friend to the Crockers. She taught cousin Will’s daughters to dance. Cousin Harriet was an early patroness and supporter in New York at the turn of the century.

Aimée had returned to America two months earlier after living in Paris most of the year at an artist commune, the Hôtel Biron, with masterminds Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Jean Cocteau and modern dance legend Isadora Duncan among other extraordinary artists. Duncan, who taught cousin Will Crocker’s daughters to dance at his home in San Francisco years earlier, took a long gallery against the garden wall, which she used for classes and dance rehearsals. Aimée, a life long dance enthusiast and connoisseur, was no doubt taking notes…

The New York World sang Aimée’s praises writing she was, “setting a pace for Terpsichore this winter that should amaze the gods on high Olympus.” Reviews were a mix of shock and awe with chastising overtones. Aimée later responded, “The Dance of All Nations at my home last month created a furor of curiosity and a little tempest of criticism proves only once again that for every one who steps out of the stupid beaten path of custom, brickbats await… The new [is] attacked and my jolly informal dance is pilloried because it was novel. The artistic will always be to some minds a synonym for wrong.” She continued:

If I had given a stereotyped reception, had stood at the door of my drawing room and extended the high hand and an icy smile to each guest then pushed them all on toward the refreshments, and nodded good night to them, how many would have been glad to see me back? Everyone would have said I wish Aimée Gouraud had stayed in Paris. She is growing stupid. It is coarse and vulgar and hideous to invite people simply to eat. An ordinary dinner is a function at which people stuff themselves until they look like crimson toads. I believe in the dance as the best form of entertainment. It entertains more than music because the appeal of music is not universal. Some persons are bored by music, others by conversation. Some are dyspeptic and prefer to eat only what they wish and that at home. But everyone likes the dance, either to join or to watch. I cannot conceive myself as giving stiff-necked, stiff-backed entertainments.

Some of Aimée’s dances were not just taboo or risqué, they were banned in certain communities, districts, even entire countries. Countless editorials, short stories, and articles condemned the dances as a dangerous violation of sexual, ethnic, and class norms. With a battering ram, the heiress Aimée Crocker Gouraud broke down doors for repressed, suppressed and oppressed women the world over on that Sunday evening in Manhattan. Crocker’s soirée was a rallying cry for pre-19th amendment, corseted women, yearning to break free from their inhibitions and restrictions.

Another dance that Crocker performed herself in 1910 is more controversial today than when it was created…

The Apache Dance

Melville Ellis. Aimée was linked to the young musician and dress designer romantically and performed the controversial Apache dance with him in 1910.

Conspicuously missing from the excentrique program was a new dance that had become the rage in Europe and was getting a foothold in the U.S.–the Apache. Aimée performed the disreputable dance herself a year before her Dance of All Nations with partner Melville Ellis at a party she collaborated on with actress Valeska Suratt.

Historically, the Apache Dance, the French pronounce it ah-PAHSH, was billed as the “Dance of the Underworld” for very valid reasons. Les Apaches or “The Gunmen of Paris” were actually savage street gangs populating the crime infested slums of Paris. The police weren’t able to suppress the underworld warfare.

Dancers Maurice Mouvet and Max Dearly in 1908 were visiting the popular Apache haunt “Caveau des innocents” on a fact finding mission when they witnessed a hoodlum get up from a poker table scattered with knives, smack a woman across her mouth, take her to the middle of the floor, and perform a peculiarly vicious and savage dance that concluded with the woman being tossed to the floor in a heap.

Where it all began, Le Caveau des Innocents

From that experience Maurice and Max created a stage combat exhibition dance described as an intense and brutal domestic fight performed in pantomime between a pimp and his whore to waltz or tango music. The woman was slapped, pushed, dragged, threatened with a knife and generally run roughshod by the ruthless, savage, violent, sadistic, male dance partner. Although a devastatingly brutal dance, it was stylized to convey primitive passion instead of vulgarity.

Max Dearly and Mistinguette performed the Apache at 1908.

High society slummers were fascinated with the dance. Maurice commented, “At the Café de Paris I was in my glory, and when I threw Leona over my head and swung her round and round, her head just missing the floor, people went mad with joy.” The dance swept Europe and launched spectacular careers for all four performers. For a while there were attempts to include it as a social dance, but its extreme physical demands and acrobatics (not to mention its overt displays of depravity) caused it to remain an exhibition dance. Because of the dangerous lifts and throws utilized, occasional horrific casualties including broken necks and backs took place. There were reports of women killed while performing.

A tamer, made for cinema version of the Apache dance 27 years after it was introduced to America in Charlie Chan in Paris (1935)

Maurice Mouvet and second wife Florence Walton in costume to dance the Apache

In the middle of April, 1910, while Maurice and Leona were dancing the Apache waltz nightly at the Café de Paris, they received a telegram from Sir Stanley Clarke requesting them to go to Biarritz to dance before His Majesty, King Edward VII. They performed for him a total of four times.

Maurice claimed not only to be the originator of the Apache dance but to be the first professional to dance the Tango in Paris, after performing it at the Café des Ambassadeurs.

Meanwhile in America, Joseph C. Smith, son of America’s first male ballet dancer George Washington Smith, said it was he who conceived the character of the “Apache” lover after several weeks study of the characters and the customs of the Paris underworld. Smith reported, “I joined them, almost became one of them, for several weeks, until I was tolerated to such an extent that I saw them as they really are and not as they have been drawn for theatrical use. It is truly awful, and yet it is life almost as primitive as in the days of cave dwellers, who live by brute force, and to whom women were slaves for the convenience and comfort of their masters—man…”

Joseph Smith and Louise Alexander performing the Apache Dance in The Queen of the Moulin Rouge (Wikimedia Commons)

He confessed that there was seldom a performance in which his partner was not bruised in the rough treatment he “necessarily” gave her. “Sometimes I know I have really hurt her, and that knowledge has almost made me stop the dance. Of course the hurt is not serious, but the bruises are real,” Smith admitted. He first performed the dance with Louis Alexander in The Queen of the Moulin Rouge in November of 1908, which also included the outrageous “Kicking Polka” performed by Aimée’s friend Reggie De Veulle.

Alexander in fact encouraged Smith not to hold back, “I do not even feel the hurts of his beating and choking me, not even when, in the final battle for supremacy between the love of the girl and the brutal instincts of the thug, he throws me actually and fearfully to the floor. It is all fine. Exhilarating, but such a terrific mental, physical, and nervous strain that I am absolutely exhausted after each performance. …My partner in the dance tried several times to go through it with less realism, and I had to beg him to use all the seeming brutality demanded by the action.”

Joseph Smith also made it very clear that he was the first to present the Tango to an American audience, not Maurice, declaring that he performed it before Mouvet’s arrival at the Winter Garden in The Review of 1911.

Joseph Smith claimed to have created the Apache dance (from The Theatre, January 1909, p 4.)

After Leona tragically died of pneumonia, a mourning Maurice decided to escape his grief by accepting an offer to dance the Apache and the Tango at Café Martin in New York, one of Aimée Crocker’s favorite haunts, with a salary of 20,000 francs a month.

Maurice arrived in America as an international figure. He was interviewed more than a visiting ambassador. A splashy full page New York Times feature appeared on the same day that he performed at Crocker’s Dance of All Nations. He was interviewed the day after giving lessons at the Plaza and the Sherry-Netherland to a Vanderbilt, a Gould, Prince Pignatelli d’Aragon and Princess Gon Faustino among others.

Aimée Crocker didn’t hire Maurice, the magnificent, to perform the Apache. Or the Tango. He instead performed La Mazurka Russe with another male, Genia Agarioff. Strange…

Later that winter season, Edmund Russell filled in the hole in Aimée’s extravaganza by furnishing the New York Bohemian/Aimée Crocker set with his “Naughty Nights Entertainments” billed as an Apache dance evening in Chinatown. Invitations stated that all the guests must come in costumes and look and act as much like Apaches and Apachesses as possible. The portly Russell wore his customary maroon plush coat and khaki trousers with a lace handkerchief in each cuff. Protruding from his silken sash were scimitars, daggers, pistols and other Apache weapons. Many devilish Apache blades came, “looking ten times as vile and wicked and cunning and desperate as the most abandoned criminals of the purlieus of Paris.” Jack’t Standing and Jose Rivera fought a dynamic duel with knives and swords, in the midst of which the lights were turned out and all the princesses screamed. Mrs. Allan-Somers cold-cocked the assembled onlookers by ushering out a grizzly bear to dance the Grizzly with. They soon discovered that the beast was weary, lethargic and nearly toothless.

Mistinguett, once the highest paid female performer in the world claimed that she was in fact the originator of the Apache dance concept. In 1919, she had her famous legs insured for 500,000 francs.

Apache dancing was on the program that evening, but no woman volunteered to participate including the ever controversial Aimée Crocker, the Queen of Bohemia. Princess Sita Devi declared that she did not believe that the Apache dance was artistic or graceful. She instead danced the Vienna Viggle.

Irene Castle, a modern ballroom dance star and rival of Maurice also didn’t like the Apache routine and its violent choreography casting the woman as the victim: “The male dancer tries to demolish the female dancer, spectacularly, and usually succeeds.” So saddled with contempt for her talented rival was Irene that she spread a floating rumor in her book Castles in the Air, that Maurice Mouvet’s first wife died while performing the Apache dance.

Mistinguett

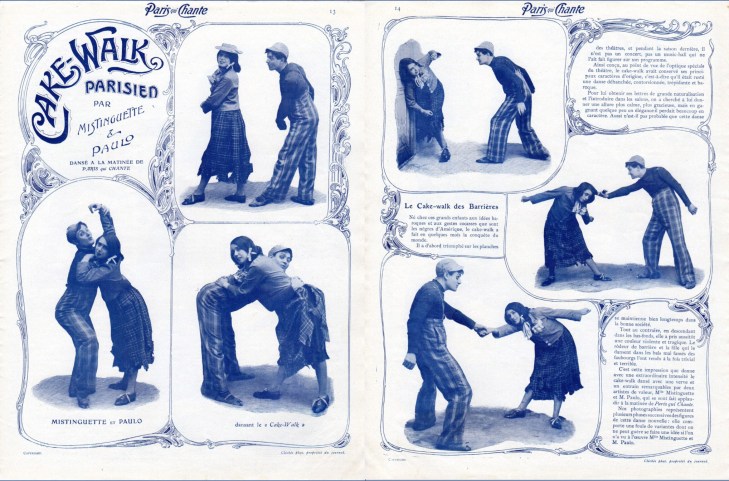

It was reported in the Boston Globe in 1919, that French actress and singer Mistinguett, born Jeanne Florentine Bourgeois, then the highest-paid female entertainer in the world, claimed that she was the originator of the Apache concept. It wasn’t her former partner Max Dearly, or the boastful Maurice or the bloviating Joseph Smith. With a Mr. Paulo as her partner, Mistinguett invented “The Cake Walk of the Barrières,” which was a mock fight-as-dance between a Parisian hooligan and a woman from the low-class Barrières, a full five years before all three male dancers.

This new dance was described, with photos, in a 1903 issue of Paris qui Chante. The illustrations show the street thug violently threatening a fearful woman and pulling her by her hair. The article described the dance as “both trivial and terrible.”

It Takes Two to Tango

Apaches en Jupons (Apaches in Petticoats) beating a victim, L’Oeil de la Police, 1908

The Apaches wreaking havoc in the mean streets of Paris were thieves and murderers, and they were also known to be pimps. Indeed, the phenomenon of the Apaches was closely linked to pimping and prostitution. The popular figure of the Apache was inseparable from that of his protege, the “gigolette.”

Among these rowdy lawbreakers in the nasty neighborhood of Goutte d’Or, who ran along the Boulevard de la Chapelle, was a bevy of particularly bombastic Apache gigolettes. Their job was to use their wiles to lure in victims who would then be pounced and robbed by their male counterparts. The violence that reigned along the boulevard was sometimes performed by the women themselves, who knew how to defend themselves, throw a punch, and wield the knife if the need arose. The press named them “Apaches in petticoats.” In the early twentieth century, when it came to the dance of violence and criminal activity in the slums of Paris, men and women, at times, worked together.

Apache street trouble lasted until the outbreak of the First World War when all known male gang members were rounded up and sent to the front line.

La Valse Chalopee by Kees Maks, 1914

The Apache dance, however, lived on well past WWI without the blessings of Aimée Crocker or Princess Sita Devi or Irene Castle. It morphed and evolved over time, becoming more comic with more and more women turning the tables on the brutish, aggressive men. At the cinema and on television the dance appeared countless times, first in 1913 in The Mothering Heart, a short dramatic film directed by D. W. Griffith. Joseph Smith performed it in 1915 in Les Vampires. Clara Bow performed it in Parisian Love in 1925. Gracie Fields performed a particularly brutal interpretation in 1934 in Queen of Hearts. Comic performances were given by Buster Keaton and Shemp from the Three Stooges, while decidedly tamer versions of the Apache dance showed up on episodes of the I Love Lucy Show as well as Krazy Kat, Mickey Mouse, Popeye and Pepe le Pew. By the sixties, when Shirley MacLaine finished performing the dance in Cole Porter’s Can Can, four men lie dead on the floor arousing uproarious applause.

Apache characters influence popular culture all over the world in cinema, art and advertising, and fashion… Top right photo shows boudoir Apache dolls (photo courtesy Robin Krueger) Bottom right is an advertisement for an Apache line of men’s clothing by Mister Freedom of Los Angeles (2011)

Aimée Crocker’s Dance of All Nations featuring as it did “primitive,” lower class and overtly sexual performances was an assault against the suffocating gender roles dominating the first decades of the 20th century. These “excentrique” dances transcended class boundaries. They convoluted racial and gender identities. They crossed borders. They dissolved age brackets. The dances told stories and promoted self expression. And artistic expression. They rejected traditional formalities. Some of these modern dances also brought women into unprecedented physical contact with their partners. Designed for arousal, they unbridled female sexuality.

By the mid-1910s American women, following Crocker’s example, had gone “dance mad” and were consorting with “lounge lizards,” “cake eaters,” “tango pirates” and “flapperoosters” who, for money and pleasure, stimulated female desires both on the dance floor and off. Crocker consorted with a 19-year-old Rudolph Valentino, who she took on as a Tango protege at Maxim’s a few years later…

Aimée Crocker’s dancers were a force to be reckoned with. Left is Nance Gwyn performing the Dance of the Seven Veils and right is Dogmeena dancing La Danse des Igorrotes.

The exhibition Apache dance may have been a bridge too far for the free loving, free thinking, free wheeling Crocker. Its display wasn’t just run of the mill misogyny. Meant to be played out as a caricature of masculine domination and female submission inside the safe and controlled framework of the theater production, a battle of the sexes in pantomime, it too often played as shear brutality against women. At Aimée Crocker’s Soirée de la Danse Excentrique, it was the fierce women that were showcased, Nance Gwyn as Salome demanding the head of John the Baptist and Dogmeena the Chieftainess killing her enemy, that would shake things up on the dance floor.

Coming soon: Part Two: The Hulu Ku’i

Part Three: The Dance of the Seven Veils

Part Four: The Tango

Selective Sources:

Aimée Crocker Gouraud, “My Original Nights,” Chicago Examiner, Jan 7, 1912, p 61.

“Bizarre Dancing Captures New York,” Detroit Free Press, Jan 14, 1912, p 63.

Castles in the Air, As Told to Bob and Wanda Duncan (Da Capo Press, 1958).

“Costume of Leaves Drops in Gotham’s Latest Dance,” The Inter Ocean, Nov 21, 1911, p1

“Dancer from Paris Introduces New Steps to Society,” New York Times Dec 10, 1911, p 58.

“Grizzly Bear Too Tame,” The Kansas City Star, Dec 11, 1911, p 14.

“How Russell Did Cut Up,” The Kansas City Star, Feb 5, 1912, p 12.

http://socialdance.stanford.edu/syllabi/Apache1.htm

https://www.streetswing.com/histmain/z3aposh.htm

Julian Street, Welcome to our City, (New York: John Lane Company, 1913).

Mark Knowles, The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances: Outrage at Couple Dancing… (McFarland & Co., 2009).

Maurice Mouvet, Maurice’s Art of Dancing, (New York: G. Schirmer, 1915).

“More ‘Art,’ Which May Mean Less Raiment, to Mark Future Soirees as Mrs. Gouraud’s ‘Danse Eccentrique’ Set Pace for Terpsichore,” The Evening World, Dec 16, 1911, p 12.

“Mrs. Gouraud as ‘La Nuit’ Does a Cobra Dance with Live Snake in ‘Soiree’ at Her Home,” New York Tribune, Dec 11, 1911, p 3.

“Optic Intoxication: Rudolph Valentino and Dance Madness,” Screening the Male Exploring Masculinities in the Hollywood Cinema Edited by Steve Cohan, Ina Rae Hark, (London: Routledge, 1992).

“Paris’ Prettiest Pair of Legs Reach New York,” Boston Globe Aug 18, 1919, p14

“Puts a Purple Edge on Things. Society Woman Basks in An Oriental Hue Spotlight. Poses as Dancer with Snake at Social Affair,” Los Angeles Times, Mar 14, 1912, p 56.

“Python Guest of Honor,” The Charlotte Evening Chronicle, Dec 4, 1911, p 4.

“The Spirit of the Dance by the Dancers…The New ‘Apache’ Dance,” New York Times, Dec 13, 1908, p 11.